OKRs sound good but they don't work (Part 1)

(Alright, they occasionally work, but nowhere near as often as you'd think.)

If you’ve been in the tech world for any length of time, you’ll have come across OKRs. (If you haven’t yet, Christina Wodtke explains them better than anyone else: https://eleganthack.com/category/high-performing-teams/okrs-2/)

OKRs are a good example of an approach that tells a pretty story about how folks think management ought to work, but that doesn’t match how management really works.

(There are many of these kinds of ideas out there. They sound nice, neat and so so simple. But when you try to put them into practice, they turn out to be painful, messy and complicated. Once you know this pattern, you’ll see it everywhere. Sorry.)

The disconnect between the simple story and the painful reality of OKRs has generated two camps:

The first camp is the people OKRs have been imposed upon. They say things like, “ugh, OKRs always suck and are done so badly.” Most of these people end up accepting that they have to do just enough to play along with OKR theatre, whilst basically ignoring the OKRs.

The second camp is the consultants who know OKRs will have made a mess and promise to unsuckify yours. They say things like, “hey, don't blame the OKR framework for your problems! I can help you make them work properly.”

Let’s dive into why OKRs can’t work in the way they promise — and why that never really mattered for their meteoric rise in popularity.

Humans don’t work in the way that OKRs want

In most of our lives, humans don’t figure out a singular explicit objective (O), then define numerical measures that tell us when we’ve achieved it (Key Results), and only then come up with some plans.

Instead, we scan a situation, do a first-fit pattern match against our past experiences, and jump onto the first idea that feels good.

Ideas that feel good are the ones that feel like they manage the risks our ancestors cared about. Ideas that feel good feel like they don’t increase our exposure to risks – especially implicitly fatal ones like being cast out of our tribe or losing status. Among the ideas that feel good, the very best ideas feel like they could plausibly help with several desirable objectives, not only one. And most desirable objectives are subconscious and personal, not conscious, explicit or tied to business metrics.

Employees avoiding personal risk

I saw this pattern of pragmatic risk avoidance play out when I coached various teams through setting OKRs.

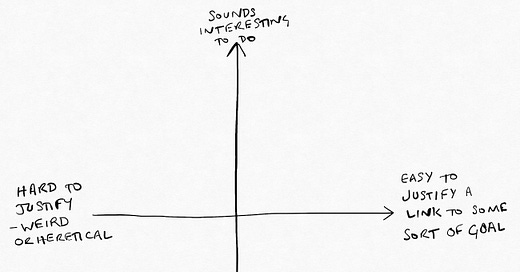

Most people had an idea or two that they just knew in their guts was worth doing next, but they were reluctant or unable to be specific about one objective that would be the result. They were choosing an idea that felt right. And it was based on juggling dozens of mostly subconscious personal goals, not on working backwards from a business objective.

Ideas that “felt right”:

were “the kinds of things that successful people with my role do”

were personally interesting, with enough-but-not-too-much challenge

could plausibly-but-vaguely be justified as helping the team and company.

At the time, it frustrated me that they couldn’t zero in on an objective so we could create some crispy OKRs. But now I see the rationale. These team members resisted specifying an explicit objective because they subconsciously felt like they would be putting themselves at risk.

Status risk

Firstly, the team members felt the risk that they might lose face — or even their job — if they didn’t achieve the objective. It’s much safer for your career not to promise results, but to get on with justifiable actions. Then you can’t really be blamed when some of these actions inevitably don’t go to plan.

The reality is that most initiatives don’t produce predictable linear results. However, they do frequently have surprising unintended consequences – both good and bad. When there are unexpected positive results, the canny operator wants to be able to post-hoc rationalise that those were the goal all along.

Derailment risk

Secondly, the team members perceived that OKRs put them at risk of being stopped from doing the idea they felt good about. Their real, subconscious reasons for feeling so good about the idea were often personal, private objectives – interest, career progression, learning, or comfort.

The data scientist who wanted to build a cutting-edge model … the engineer who wanted to experiment with a new strongly-typed language … the designer who wanted to fix a usability snafu (guilty as charged) … what if they pinned down an OKR that contained their idea and then an executive decided that OKR wasn’t worth going after? Or made them do something different to achieve the objective?

Execs avoiding risk

I saw a slightly different flavour of risk avoidance playing out when I worked with executive teams to help them set company-level OKRs.

In those cases, it was even more obvious that they wanted to hide their real objectives.

Often, a company’s real objectives have to be kept secret (i.e. not plastered all over the walls and shared in every meeting). For instance, many exec teams urgently need their business to “become investable”. But you can’t say that out loud! Not only does it sound uninspiring to the troops, it also makes you sound desperate — and therefore uninvestable — to potential investors.

What’s more, often the execs’ real objectives are unpalatable. Stating them clearly might expose the fact that three quarters of the workforce won’t be doing anything particularly valuable this quarter. Or the objectives might involve preparing to shut down a department … or worse.

So instead, the execs craft nice-sounding but deliberately vague OKRs that give everyone something to keep them busy. Then they micromanage a handful of teams to work on the real objectives (often even contradicting the official OKRs).

Naïve?

At this point you’re probably thinking, “Christ on a bendy bus, Tom, are you really this wet behind the ears? Of course this is how businesses use OKRs!”

Let’s just say I’m writing this post to my younger self, hoping he’ll stop believing that OKRs are really supposed to do what they promise.

OKRs aren’t for getting results

In the end, none of the mismatch between how things are supposed to work and how they actually work matters.

Business leaders don’t impose OKRs because they’re effective at generating business results. They impose them because they’re a safe choice. They look tidy to investors, they’re logical for continued employability in the C-suite, and they make it look like you’ve done strategy when you stuff them into presentations.

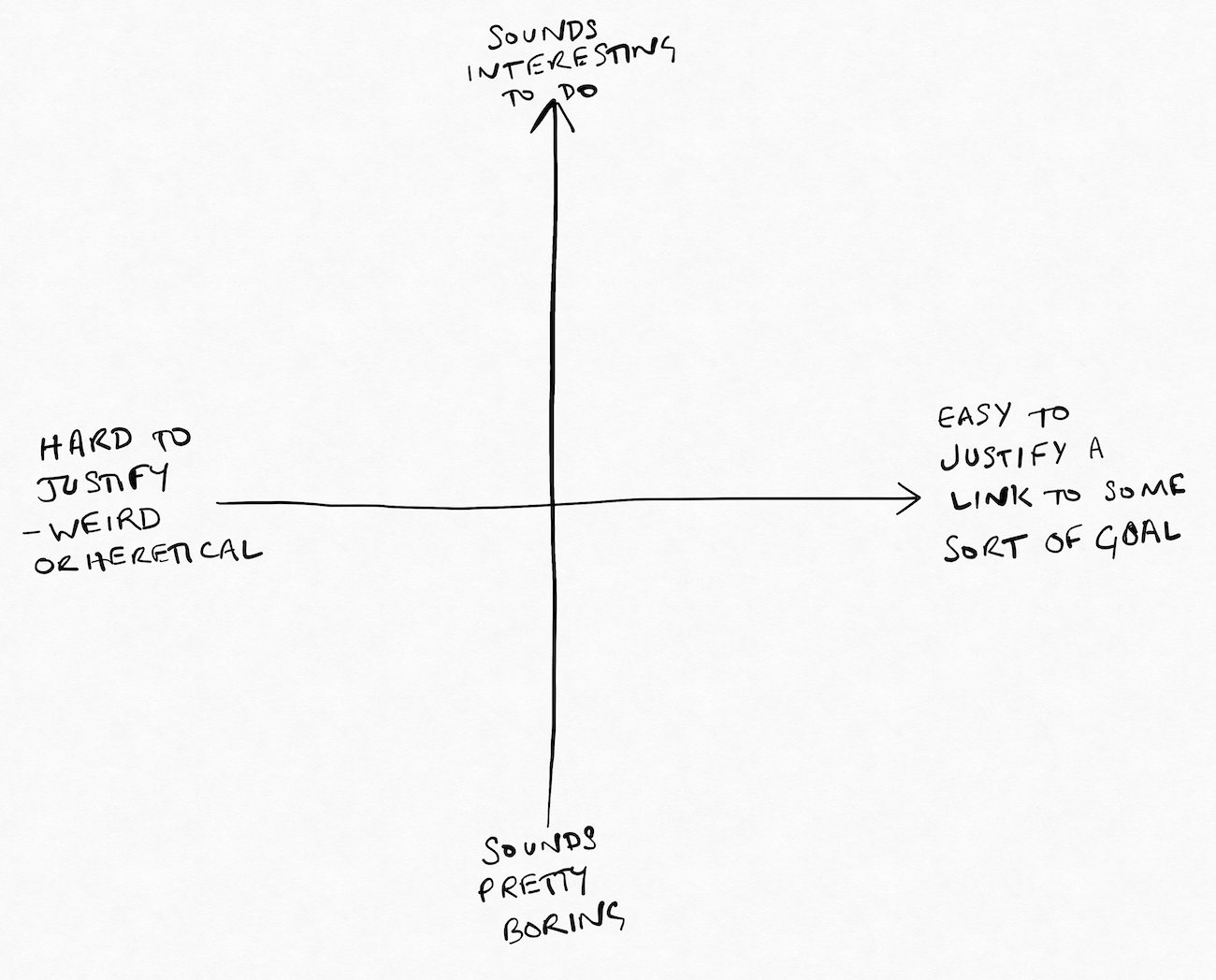

In short, they “feel right”! They:

are “the kinds of things that successful execs with my role do”

can be personally interesting, with enough-but-not-too-much challenge

could plausibly-but-vaguely be justified as helping the business.

Sound familiar?!

So whether or not OKRs generate results is by-the-by. That’s not what they’re for.

I know this is controversial. Maybe I’m just a hater? Maybe I never liked them because I never saw them done properly?

Not at all! 10 years ago, I was all-in on OKRs. I read all the books, spent energy coaching teams and execs, and even used personal OKRs outside of work.

OKRs are effective … in a certain sweet spot

I recall one 3-month period when a team I was leading had an OKR and it was great.

We had:

a specific, tractable problem evidenced by lots of user research

within an otherwise stable and well-understood process

that was also easy to measure

with a constrained range of options that we could try.

Because this happened during a reorg, we fell between the cracks and lucked out. We had 3 months off the critical path to focus on the OKR, and also total freedom to set our own OKR.

In those 3 months, one of our A/B tests ameliorated the problem in a surprising way, making customers happier and the company millions. (Our reward? The experimentation program was put on hold indefinitely. Woo!)

So yes, one time out of literally dozens, an OKR worked.

Every single other time, the OKRs have been bullshit, gamed, a wish-list, or a task-list.

Whether OKRs will work for you is 99% down to your context. And in most contexts, you’ll find that growing camp of people saying, “ugh, OKRs always suck and are done so badly.”

OK, so what if you want to stop using OKRs?

Then you’re going to hit the ultimate hurdle.

It’s hard to stop doing something — even if it’s ineffective, or even harmful — if you can’t provide an easy, comfortable alternative.

LOL we can’t just do nothing! How will we control peop ... ahem ... give our valued employees strategic goals to support their career progression? How will we align teams [into blind lockstep]? And how will we hold those lazy people over there accountable [for not doing what we told them]?

So even if you can persuade someone that OKRs are ineffective and harmful, you’ll also need to give them an alternative that feels easy and comfortable. That “feels right”.

I have an alternative for you. Find out more in part 2 of this series.

Tom x

Coming back to this after a while, but I think I loved it more than the first time I read it!

On this line -

> the team members perceived that OKRs put them at risk of being stopped from doing the idea they felt good about.

Are you referring to a simple conflict on what the team is looking to work on, against what was basically passed down to them as a directive, disguised as an OKR? Or is there another nuance in there that I'm missing?

Very timely, Tom! I will share some of your acerbic wit with a "value management office" this week.