Objectives, the adjacent possible, and teaching sign-language to bears

Part 2 in the "OKRs sound good but they don't work" series

This is part 2 of my OKRs series. Here’s part 1.

I was aiming to share some solutions today but actually, that’ll come in part 3. It turns out things need to get a bit juicier first.

Housekeeping

Looking for help with: strategic coaching, team training, workshop facilitation, or diagnosing design problems? Grab a free 25-minute coffee chat to see if we could work together or buy an instant consulting hour to get results right away.

Get 10% off my Innovation Tactics card deck using my referral link (which also gives me a little kickback, ta!): https://bit.ly/innovation-10

Not all objectives are created equal

I vividly remember one client who designed, manufactured and sold sheds that were delivered in pieces for their customers to put together. To anonymise them, let’s call them Sheds Inc.

Sheds Inc. were struggling with seasonal dips and spikes in demand, which caused all sorts of inventory and cashflow headaches. So when they hired Conversion Rate Experts, one of their objectives was to figure out how to level out demand across the year.

Do you see the flaw? Visualise yourself manhandling shed panels while being blasted with horizontal sleet. Yes, unfortunately, only the hardiest (or most desperate) shed customers even consider buying a shed in winter, especially a self-assembly one. There’s no magic A/B test or offer that can fix that.

As it happened, Sheds Inc. quickly saw the light and accepted reality. They got amazing results from other tests, which in turn opened up some new possibilities, which in turn could help with the lumpy cashflow.

For Sheds Inc., their objective to “smooth out seasonal demand” was highly desirable, but it wasn’t achievable. It wasn’t in their adjacent possible.

The adjacent possible is a concept coined by Stuart Kauffman (here’s a 9 min video). It describes the set of possibilities that are available to an individual, organism, community, or organisation at a given point in time during their evolution.

In other words, it’s what you can do next – whether or not you want to do that, or even know about it. Your adjacent possible changes all the time, as both you and your context evolve.

When we set an objective — at company level or personal — we’re seeking to do something. We’re hoping that what we want to do is inside our adjacent possible. But figuring out whether it really is? Well that’s not as easy as it might look at first glance, which has implications for OKRs.

Let’s illustrate this by looking at some simple examples of objectives.

I’ll start by outlining some personal objectives I entertained just now as I consider my 2024 strategy:

make 10 million quid

become a professional footballer

write a book

travel around Japan

teach sign language to a bear

have 10,000 subscribers to my YouTube channel

sail around the world

open a coffee shop

…

When it’s a personal list like this, it’s obvious that some of these are ludicrous. And yet I’ve seen many a corporate presentation packed with an equivalent set of bullet-pointed wishes.

The list exposes three types of objective from worst to best:

Objective type 1 (worst): Not even possible, let alone adjacent

Some of the objectives are clearly nowhere near my adjacent possible. I’m too old to be a footballer, and heroically incompetent at football to boot. And a quick search revealed that bears almost certainly can’t learn sign language.

These objectives are not coherent with reality, so I shouldn’t waste time on them.

Thinking back to Sheds Inc., their objective was similar to ‘teach sign language to a bear’, though admittedly less likely to end up with someone being mauled.

We can usually reject this kind of objective with a little thinking about human (or ursine) behaviour. The sort of thinking that’s surprisingly tricky to make time for in an organisation.

Objective type 2 (better): Possible but not adjacent

Most of my objectives are in the next — and most dangerous — zone: a step or three beyond my adjacent possible. They’re not obviously silly, but there’s an explosion of unknowns.

For example, getting to 10,000 YouTube subscribers. For someone with 9,500 subscribers, this would be adjacent possible. I’m not someone like that. I don’t even have a YouTube channel to speak of. But I could totally make one. And then — with a lot of luck and a following wind — maybe I could get to 10,000 subscribers in 2024?

Maybe. But a heck of a lot can go awry along the way. From where I stand today, I don’t know enough to know what the steps after ‘make a YouTube channel’ will truly involve. It will likely turn out that, no, I actually can’t get to 10,000 subscribers. Perhaps I don’t (yet) have the capabilities I’d need. Perhaps I have too-niche a topic? Or not niche enough? Perhaps I’ll hit 100 subscribers and realise I don’t want to do this any more? These are just the factors I can think of today. There are loads more I can’t even know about yet, because I’m not in the context where they’ll show up.

I worked with one SaaS company whose objective was to increase frequency of use of their app. Previously they had run dozens of experiments and even released whole new features, all focused on frequency of use. Nothing had really moved the needle. I did an alternative form of analysis and it revealed that greater frequency of use was probably not an adjacent possible for them. With their existing user base and their context, they were already maxed out. To achieve their objective, they’d have to start from a different place.

This reminds me of the classic joke about a tourist in Ireland who asks a local for directions to Tipperary. The Irishman replies: “Well sir, if I were you, I wouldn’t start from here”.

An awful lot of corporate objectives fall into this zone. They’re not directly achievable from where you are today. They hide a linked chain of intermediate steps, each of which could go wrong or change our understanding of what it actually takes to achieve the objective. Or even change our desire to achieve the objective at all.

Objective type 3 (best): Both possible and adjacent

Other objectives look like they’re slap-bang in my adjacent possible, and feel like a no-brainer. Obviously, I could just write a book, or just book a trip to Japan.

Finally! Some objectives we can comfortably get behind!

But not so fast … possible is not the same as probable. Even in the adjacent possible, plans often don’t pan out.

Firstly, circumstances can change. My partner and I had an objective to visit Japan. We were all set and determined to make it happen. In 2020.

Secondly, we can’t know what’s truly possible for us upfront. I’m pretty sure I could write a book in 2024, but I might try for months only to find out I’m actually not up to the task. Or I might succeed, only to realise it was a waste of my time.

In the meantime, I risk overlooking other adjacent possibles I can’t perceive yet.

For example, when I started 2023, I hadn’t really considered speaking at a conference, and yet talking at UX Brighton earlier this month was a highlight of my year. That opportunity came from a 5-minute email that I dashed off on the spur of the moment. Perhaps that was only possible because I wasn’t focused on writing a book!

In business, focus is talked about as if it’s obviously the right thing to do. And sure, often it is. Just know that focus is a tradeoff. The tighter your focus on one part of your context, the less able you are to notice everything else. If you’re laser-focused on a distant vision, it’s easy to stumble into pitfalls in front of you, or to miss better opportunities that pop up along the journey. If you’re laser-focused on a single tree, it’s easy to neglect signs that you’re in the wrong forest.

So which objectives are adjacent possible?

Success with any objective always depends on some behaviours of people and systems outside of your control.

For an objective to be comfortably in your adjacent possible:

you’ll have a range of promising ideas, which gives you more chances to achieve the objective

your ideas will depend on influencing only one critical behaviour outside your control

that critical behaviour will be relatively easy to generate or change.

And each of the following factors moves you further from the adjacent possible:

you have relatively few promising ideas (or even none)

your ideas depend on influencing several critical behaviours outside your control

one or more of the critical behaviours is hard to generate or change.

This is a simplified heuristic. It won’t guarantee success. But it’s a quick way to sense-check your objectives and ideas.

How to identify the critical behaviours your success depends upon

Pick one of your objectives

List a few ideas you have that might help you reach the objective

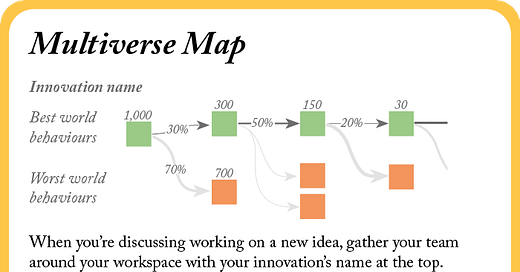

Take 5 minutes to make a Multiverse Map of each idea (this is a method from Innovation Tactics and I’ve included the instructions at the end of this article).

This process helps you think through what you’ll need people in the real world to do for you to meet your objective. And you’ll get wonderful clarity by starting as if your success depends on only one person. What’s the very least that you need that one person to see and do? What are you expecting from a customer or a colleague? What are you expecting from yourself?

If your idea won’t interface directly with humans, you can also map the technical systems you’ll depend on: third-party software, services, APIs, data, etc.

In particular, notice when an apparently simple objective smuggles in other behaviours that you’ll need to consider.

For example, if I’m going to write a book, I quickly feel a tickle of panic at the critical behaviour I need from myself. That’s to sit down and do all the keyboard tapping. But by focusing on the writing, I can easily bury my head in the sand and “forget” that I’d also need someone other than me to find, choose, buy, read and enjoy the book.

It’s a common pattern on tech teams to focus on building the thing and hand-wave away all the stuff about customers finding it and choosing it. But the behaviours are inextricably linked. The way you make it shapes how you’ll sell it; and the way you sell it shapes how you’ll make it. The solution is intertwined with the distribution.

Look across the maps you made and notice common themes in the behaviours you’re going to rely on. Can you strip back your ideas? Remove or work around any behaviours? I often think of new, simpler ideas once I’ve mapped the obvious ones.

If you’re accustomed to thinking in supply-side abstractions like funnels and metrics, this exercise will give you a fresh perspective. The map gives you a glimpse of what things look like from the market’s viewpoint.

Now you have a list of ideas and behaviours, you can use the heuristic above to get a sense of how adjacent and how possible your objective might be.

By the way, even if your objective is way outside your adjacent possible, you may still want to pursue it. I’m not going to tell you anything’s impossible, just that you might need to take a more winding path to the objective than OKRs would typically have you do.

Perhaps you might start by tackling only the toughest behaviour and leave the rest for later? Or you might even want to work on the conditions around the toughest behaviour, so you first make it easier or less necessary.

Or you may need to start with a smaller objective that will teach you more about what you’re really dealing with.

Instead of dropping my life savings on opening a coffee shop, maybe I should consider first training as a barista, then trying my hand at running a portable coffee cart.

What can you actually get done in a quarter?

Another big factor in what’s adjacent possible for you is your capacity.

After part 1 of the OKR series, I heard from:

someone whose team was empowered to focus on just 2 OKRs each quarter – and ignore everything else

someone who figured the expectation was that OKRs would magically squeeze more work out of teams, on top of everything they were already buried under

someone whose team was given about 100 OKRs every quarter

someone who described their company’s approach to OKRs as “management decide what they should be. Our method for tackling them is PMs dramatically say them out loud to the team more often as we get near the end of the quarter”.

I’ve worked in places all over that range. In one extreme, it took at least the first month of each quarter to set and agree each team’s OKRs, so a quarter was really 8 weeks. Then we analysed the team’s ongoing workload. Once you’d factored in maintenance, bug fixing, business-as-usual, regular meetings, holidays, overheads, etc., it turned out the team had a grand total of 2.5 days available to complete their OKRs. That’s less than one day of work for each OKR … I don’t think I need to tell you how much progress we didn’t make.

So take an honest account. Draw it on a calendar. How much time do you really have to work towards each objective?

So what can you do about OKRs?

I’m aware that this has been painting a bit of a bleak picture so far. Spoiler alert, it might get bleaker before it gets better. In part 3, we’re going to accept OKRs but gently disrupt them by shifting them into AOKRs: Adaptive OKRs.

For now, go forth and map your multiverse!

Thanks to the anonymous folks who contributed their stories, and to

for helping me make this make sense.Work with me!

I’d love to help you Multiverse Map your situation and resolve your strategic challenges around setting and hitting your objectives. Might you be trying to teach sign-language to bears?

Grab a free 25-minute coffee chat to see if we could work together or buy an instant consulting hour to get results right away.

Lastly, you can get 10% off my Innovation Tactics card deck using my referral link (which also gives me a little kickback, ta!): https://bit.ly/innovation-10