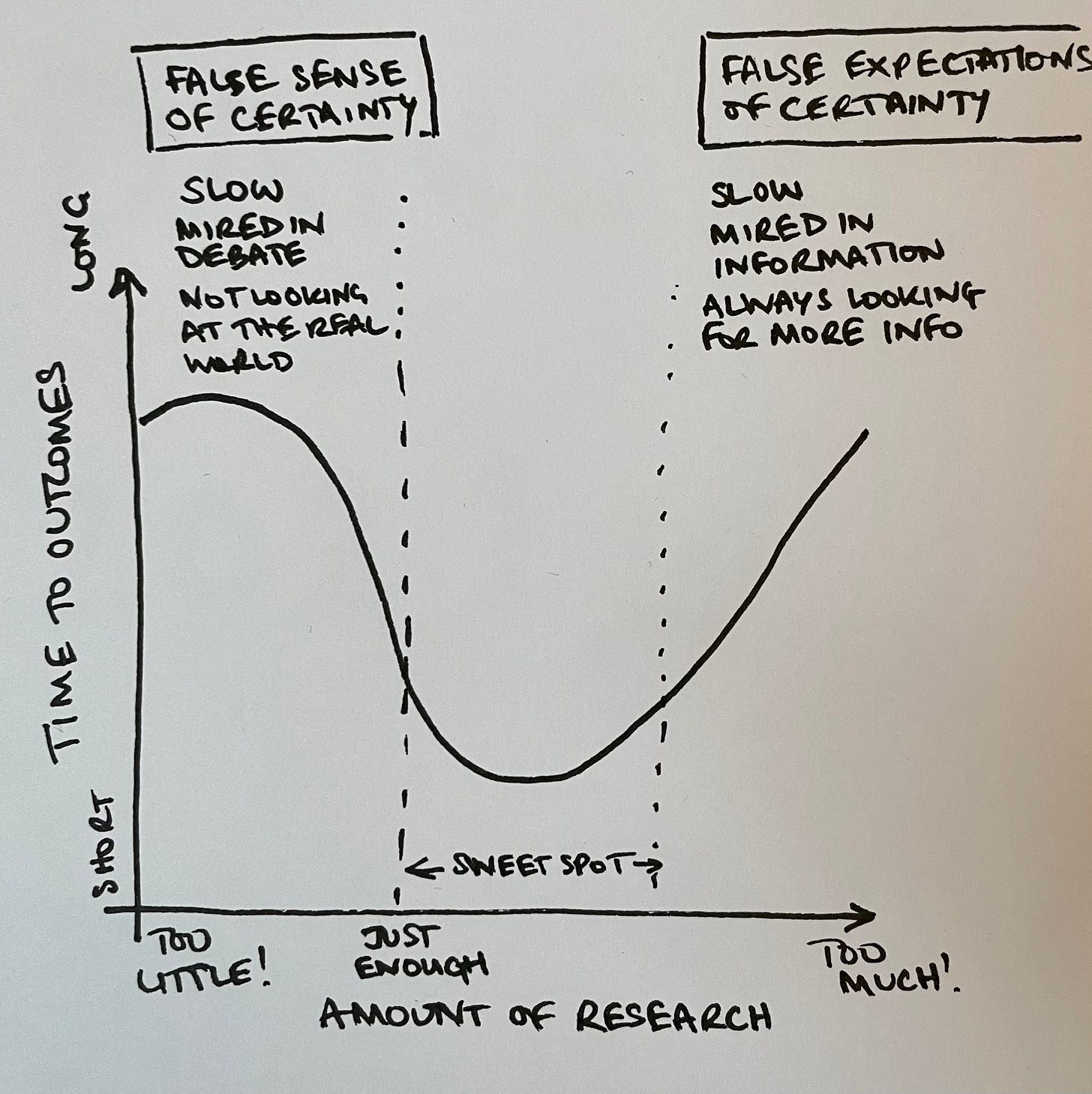

How much research is just enough research? How much is too much?

A graph that popped into my head when I couldn't sleep one night

Here’s the graph:

What’s going on here then?

On the left of the graph, we’re doing too little research

We’re trapped by a false sense of certainty. We believe we’ve got The Answer™ … but really that’s because we don’t know any better and we aren’t looking for evidence to the contrary.

This is a common place for teams and companies to end up. I know I’ve been there.

You might recognise: …

… when you’re all totally bought in on all Steve Blank’s Build-Measure-Learn approach, and know you need to Get Out Of the Building … but in practice you’re only really doing the Build part, and you keep putting off the pesky Measure and Learn parts till later.

… when the boss says, “we don’t have time or budget for research, just build!” (Of course, the same boss wouldn’t buy a $50k car without months of research and test drives … but apparently thinks nothing of setting fire to $5m of company funds on a their genius hunch.)

… when your teams spend weeks debating over every minuscule detail of a process, while also failing to question whether anyone even wants the result of that process.

This leads to building “brilliant” things … that nobody wants. High profile examples you might’ve heard of include Juicero, Quibi, and — probably — that recent project your team’s been working on.

Of course, some bright spark will always pop up and point to things that people did want against the odds and (apparently) without doing any research. Remember that luck is always a factor, and survivorship bias is basically a prerequisite for hustle culture.

The point is that without research, it takes longer on average to get the desired outcomes. Why? Simply because we’re going to have to build all the things that don’t work as well as the things that do before we can work out which is which.

On the right of the graph, we’re doing too much research

Here, we’re trapped by false expectations of certainty. We wait to gather more data, analyse more information, hoard more evidence, until we know exactly what to do.

We’re looking for a guarantee that what we build won’t fail. But no such guarantee exists.

What makes this even worse: the more evidence we gather, the more conflicting evidence we find. When we seek more certainty, we end up with less.

And the longer we wait, the more certainty our brains need to break the deadlock. So we always feel we need “just one more” study, “just one more” round of research …

The time to outcomes on the graph shoots upwards because we get stuck in an analysis paralysis vicious cycle.

In the Research Sweet Spot, there’s an interplay between research and action

Here we shoot for about 70% confidence, take a little action, and then repeat.

Here we work Fast, Inexpensive, Restrained and Elegant (F.I.R.E.).

Here we accept that we can’t predict the future, but that we can make better decisions.

And we learn to make better decisions by creating tighter feedback loops: hours and days, instead of weeks, months or even years.

So we cross the river by feeling the stones: take one small step in broadly the right direction, and sense whether we can balance there to prepare for the next step.

We can feel when we’re in the research sweet spot, because it feels like we’re playing the game with the cheat code enabled.

However, like any superpower, it comes with a cost we can’t ignore: the emotional cost of finding out we’re wrong. A lot. And that’s difficult.

Helping us get to and stay in the sweet spot is what I designed Pivot Triggers to help with. One reader described the approach as leading to “… a great discussion, challenging the team to think critically about the purpose of each of our efforts … I feel that just the act of setting [Pivot Triggers] gave the team a certain perspective on outcomes over outputs.”

Getting to just enough research takes practice

Did you notice that I drew the time to outcomes line going up a little as the graph moves from absolutely zero research to a little bit of research?

I didn’t originally plan it like that, but I think it’s true that when you get started with research, you’ll slow a little before you speed up.

There are 2 reasons for this:

1) Being wrong is emotionally hard

At first, you’ll be slowed down because your organisation isn’t prepared for being wrong. As one person memorably told me: “the problem with research is that it either tells us we’re building the wrong thing or building the thing wrong.”

If this is left unhandled, it can lead to an unhappy pattern where research is coopted to seek “validation” for pet theories.

“Validation is often systematised confirmation bias dressed up in genuine inquiry’s clothing.” – Me

2) It takes time and energy to build a research habit

Lots of companies treat research as a once-in-a-blue-moon affair, and then give up when their sophomore efforts don’t immediately deliver amazing outcomes.

But nobody expects to be good at most skills on their first go, nor if they only practise a handful of times a year. It takes time and energy to get started with research, and you’ll have to do a few cycles and get in some reps before you’re in the swing of it.

Imagine you’ve never played tennis, and I challenge you to hit an amazing tennis shot next week.

You can spend all week planning the shot, mapping out all the possibilities you can think of. Then you step onto court and take that one shot. What are the chances that you’ll manage a decent shot, let alone an amazing one?

Or you can spend the week differently: you can spend time every day hitting tennis shots. When you step onto court, you’re going to have a massively better chance of hitting a good shot. But it gets even better: you’re going to be allowed to choose which shot you want to count.

Research is a bit like that. It takes practice before you get smooth and capable. And you can never guarantee exactly which research effort is going to give you that valuable insight you need (whether positive or negative) – so it’s better to take a lot of shots. Ideally, do a little research every week.

We get to our desired outcomes fastest after we’ve built a continuous research habit and developed our emotional resilience – so we keep taking action and keep looking for where we’ve got it wrong.

Thanks to Corissa Nunn for editing genius

![[DEPRECATED] Trigger Strategy has become The Reach](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CChb!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd6524a40-bedd-4b02-b1e6-d9adac56fa1b_850x850.png)

![[DEPRECATED] Trigger Strategy has become The Reach](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0a1A!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3d932af5-2274-4840-8a79-d4ee229a2a91_1344x256.png)