Tumbling into the Vision Chasm - Part 1

Why vision is a double-edged sword

Oh hey there,

Writing this one started to feel like I was trying to hold too much sand in my hands, so I’m breaking it down into a series. In this series, we’re going to explore what I call The Vision Chasm. I’ll share how companies tumble into it, suggest alternatives that don’t involve setting visions, and arm you with some grappling hooks and crampons so you can climb out of the chasm if you find you’re tumbling down there.

In part 1, you’ll hear the story of a vision that worked superbly until it didn’t – and the visionless initiative that saved the day.

First, let’s meet the Vision Chasm.

Introducing your new frenemy, the Vision Chasm

Here’s what most books, LinkedIn thinkfluencers and consultancy frameworks tell you is The Way to Do Strategy™:

Define the vision – where you want to get to

Work backwards to figure out the strategy: the steps to get there from where you are now, with phased objectives, milestones or targets

Communicate the vision and strategy compellingly to get everyone aligned

Execute! (With some monitoring and adjustments so you stay on target.)

Any given book or consultant might include a few more steps, or use more fanciful words, but most claim that strategy has to follow this sequence.

Well I’m here to tell you that they’re wrong. There are other ways to strategise that don’t require you to define a vision upfront. And I want you to have those in your strategic tool belt too. Because if you rely on vision-based strategy when it’s not appropriate, you’re gonna tumble into the Vision Chasm.

I first used the term Vision Chasm in a 2022 interview for Strategy in Praxis:

The leadership believe they need to set a vision and mission, to define what they’d like things to be in three years; usually, this is “all the complaints and restrictions that are annoying us today have magically gone away”. Meanwhile, all the people who are doing the work have a clear picture of what they’re doing for the next three weeks, but no idea how anything they’re doing relates to the magical vision.

And, crucially, there’s rarely anything in-between. That’s the vision chasm. People try to fill this chasm with planning, like road mapping. A narrative around social beliefs tends to become the currency that gets work onto said roadmap – which needs a sort of shutting out of reality in order to protect these beliefs long enough to get something done.

OK let’s make this all a bit more crispy with a story.

Story part 1: the double edges of vision

Let’s travel back to the before-times, those halcyon days when nobody knew what COVID was, when tech was still pretty exciting and VC money was sloshing around startups like cheap beer at a student party.

Our CEO at the time shared the following urgent situation and his compelling vision:

“Our current service is at the end of its lifecycle because the optimisation market is nearing the end of its S-curve of growth. To survive, we will have to make a daring jump to the next S-curve. That’s going to be personalisation. And our vision is to provide our customers with a simple, powerful product that enables them to personalise their customer experiences, which will enable them to unlock new growth.”

This vision was believable, informed by industry analysts, and supported by customer research. It hadn’t been cooked up in 5 minutes. It was shaped, crystallised and elucidated by capable, informed experts over years.

This vision aligned teams toward the destination. It enabled us to set objectives and break up deliverables into a clear plan.

This vision was compelling. It got teams fired up and moving.

Nine months later, a new product was launched. It looked swish, worked well, and nailed the vision.

So far, we’ve been seeing the light glinting off the good edge of the vision sword. Alignment! Action! Progress! And these are not to be sniffed at. Many leaders would be delighted to have them in any form.

But of course a double-edged sword has a bad edge too.

The bad edge was that the vision didn’t actually come true and the product didn’t sell.

It turned out that personalisation actually wasn’t the next big S-curve. Most companies that tried personalisation saw tiny incremental returns that didn’t cover the extra effort required. And personalisation depended on so many conditions inside organisations that no third-party product could scratch the surface.

All this was only clear with hindsight.

Now you know it too, you might be thinking, “but those failures of personalisation are obvious, Tom. You should have seen all that from the beginning!”

We couldn’t have. And you can’t either. Here’s why:

Retrospective Coherence is almost certainly messing you up

All the stories you read about brilliant visions that worked out, they were written afterwards, with the benefit of hindsight.

“This is the way that [cool company] won. Copy them and you can win too!”

– LinkedIn Thinkfluencer

Partly, you’ll recognise that this is a story of survivorship bias: you don’t even hear about the many companies who set a brilliant vision just like in the books … and then didn’t survive.

But there’s something more subtle at work too. The stories you read about brilliant visions that worked out … they didn’t actually happen that way. The people who succeeded aren’t telling you how things really went down. This isn’t malicious or deliberate, it’s just retrospective coherence. After either success or failure has happened, humans unconsciously and unintentionally reframe our memories of what happened to fit a helpful narrative.

Retrospective coherence might be familiar to you from a famous Steve Jobs quote:

You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards.

You probably already know this in your life in general. Think of the best things in your life. How many of those things were planned in advance? When I ask most people, the answer is, “approximately none”.

For example, most people in a happy relationship can tell you the story of their “meet cute”1 – the particular combination of coincidences that form the origin story of their partnership. You know that every couple’s story is at least partly fabricated, with many dots left out and other dots massaged. Their happy “meet cute” is an example of retrospective coherence. Listen between the lines, and it probably tells you a lot more about the current state of their relationship than it does about how they really met.

Later, after the couple break up, especially if the relationship turned bad, each person involved will unconsciously rewrite their “meet cute”. From a new perspective, they connect a different set of dots, and massage their story in a different way. In the new version, it turns out they always knew their ex was trouble and they’re kicking themselves for not joining the dots to see the obvious red flags everywhere.

And it’s the same with all projects at work. You can only see how the dots joined up when you’re looking backwards. The way you join the dots will be different depending on how you feel about what transpired: good, bad, ugly. The way you massage the story will depend on what you’re using the story to do now: to explain yourself, to make yourself feel better, to beat yourself up, to teach, to persuade, to sell, …

Ah, to sell! This brings us back to the strategy books. Why do they make it sound like success involved a strategically brilliant leader who analysed the situation, identified the path to the promised land, rallied the troops, executed and succeeded? Because it sells the dream: you could be that strategically brilliant leader, if you only pay $$$ and follow our 5-steps to success!

(Quick aside: I’d love to help you be a strategically brilliant leader without the simplistic 5-step frameworks. Get in touch to ask me about coaching and training.)

Unselling the dream of the vision

So here I am, telling you the story of a vision that went wrong from another place of retrospective coherence. I’m joining the dots in a particular way, telling you a story to sell you my perspective.

Perhaps you think I should simply tell you the whole story of what really happened in the situation I described earlier. If I lay out all of the data, then you can come to your own conclusions.

Except that telling the whole story would mean recreating all of reality over a period of more than a year. Even if I could do that, I’m going to say that’s probably not a good use of my or your time.

We’re doomed to retrospective coherence, but also we’re blessed by it. Compressing stories of past cases is a way that we learn and communicate. Just don’t make the mistake of believing that hindsight can give you foresight next time. Next time things will play out differently. And that’s a lesson we can all learn.

So think back to the story I told above about the CEO’s vision. When he set the vision, he couldn’t have known what was going to happen, and neither could you. There were far too many dots that could be joined in different ways. Far too many potential wrinkles and eventualities in any future vision he might choose.

Any point in time when you set a future vision is the point in time when you know the least about how the future will play out. Given this, it should be no surprise that your vision is going to be wrong.

So what are you supposed to do instead? Surely you can’t just have no vision?!

To find out, let’s jump back in to the story, right at the point where we had lost faith in that vision of jumping to the personalisation S-curve.

Story part 2: visionless is not the same as blind

As the personalisation vision I mentioned in part 1 fell apart like wet tissue paper, retrospective coherence kicked in. Suddenly, we couldn’t help but join a new set of dots. We now talked openly about classic not-that-into-you signals that we’d been mostly ignoring or quieting. Like when a potential customer said, “looks cool, but can I sign up next year instead?” We could now see big practical obstacles to adoption that we’d been overlooking when our gaze was locked onto the faraway vision.

Some things did come true though. One thing that was more true than ever was the looming end of the optimisation product lifecycle. This company needed to try something drastic, and soon. The CEO sent a small team off on an exploratory scouting journey. This team, now freed from the blinkers of vision, instead worked directly with the current situation of the users we wanted to support.

We dived deep into the details of our users’ actual work lives. Their lives were messy and contradictory and bursting with far too many dots to tell a simple vision story about. Instead, this investigation inspired a huge number of small ideas. We framed those as many potential promises to fix minor-but-real weekly grumbles. Think of this set of diverse promises as a way to explore many competing micro-visions at the same time, instead of needing to align to a grand vision.

These promises helped us start many small journeys over about a month. We shared different concepts with users in a lightweight way, and we started to notice more energy gathering around some directions and less around others. What emerged was a direction we wouldn’t have ever considered.

In a weird twist, the energy directed us down a path the CEO had already trodden. They’d built and launched a product 5 years earlier in exactly the direction we were now considering. Back then, they hadn’t been able to get anyone to use it and gave up on the idea ... but now we had signals that there could be a “there” there after all. We tested an advert that generated real sign ups on a landing page. This was low volume, but was already more interest than we had for the personalisation product.

Treading a little way further down that path, we spent 2 weeks prototyping a concept. We worked directly with a consultant who had worked in the job our users had, and co-designed a unique visualisation that gave users a fresh perspective on the performance of different products sold by their business. This visualisation fulfilled the promise we wanted to make, and it looked seriously cool.

We plugged in real customer data and showed it to those real customers. They hated it.

Now we were really puzzled. This was something people in this role had signed up for, we’d designed it with someone from the role, and it was still wrong. We shouldn’t have been surprised: we’d got carried away with a vision of what would be cool – of course it was going to be wrong.

A few dismal weeks after that first failure, we stripped things right back and tried something that felt ridiculous at the time. In 8 days, we hand-made a spreadsheet each for 30 of our customers. It displayed a relatively tiny amount of data in quite an ugly way. We threw in some basic graphs. The designer on the team wept.

We sent out the first batch by email to real customers, expecting nothing. They loved it.

Over the following 10 weeks, working directly with the customers, we evolved that ugly spreadsheet. We added and removed bits of data. We tried to get them to leave notes in it (they didn’t). Sometimes we redesigned the whole thing. We tried to get the m to take action (they did).

Every Monday morning, our whole team got up at 6am to send real data to real customers in time for them to use it. We paid attention to who was using it, what they did with the information, and how those decisions worked out for them. After 10 weeks, it was slightly less ugly, and the rate at which we were making changes had slowed right down. Our developers and data scientists had worked in the background so that instead of it taking 8 days to put it all together, it was now nearly all automatic. We’d co-evolved a valuable product with real customers in real time.

The product we evolved was something the company wouldn’t have put on a roadmap. And the design of that product ended up nothing like anyone could have dreamed of when we started making it. By the end of the visionless exploratory journey, we understood what our customers actually needed, and we knew why our first prototype had bombed. Retrospective coherence was on our side, and we were able to confidently design something beautiful and valuable. I recently heard that it’s still being used in the same form today.

This story reflects a theme I’ve seen many times throughout my career. The successful projects have always changed along the way and ended up somewhere surprising. The failures stuck to the initial vision.

What doesn’t come across well in a story told like this is just how uncomfortable this journey was. Sure it was punctuated with excitement and insights, but also confusion and disappointment. The handful of paragraphs above cover months of wandering without knowing where we were going to end up. I’ve left out some dead ends we had to explore and times when we were stuck in deadlocks, so it reads as if it was much cleaner and more linear than it really was.

Uncertainty is generative, but it’s also painfully uncomfortable. And we were (finally!) grappling with the reality of uncertainty ... and the uncertainty of reality.

Without a vision to march towards, we just had to take the next step down a dark, foggy path. And then do that again and again.

All we could do was the next right thing.

Wrapping up

This story and conclusion hints at some of the ideas and themes I’ll cover in more detail in future parts of this series. Next time, we’re going to talk more about what being in the Vision Chasm feels like for different people in an organisation.

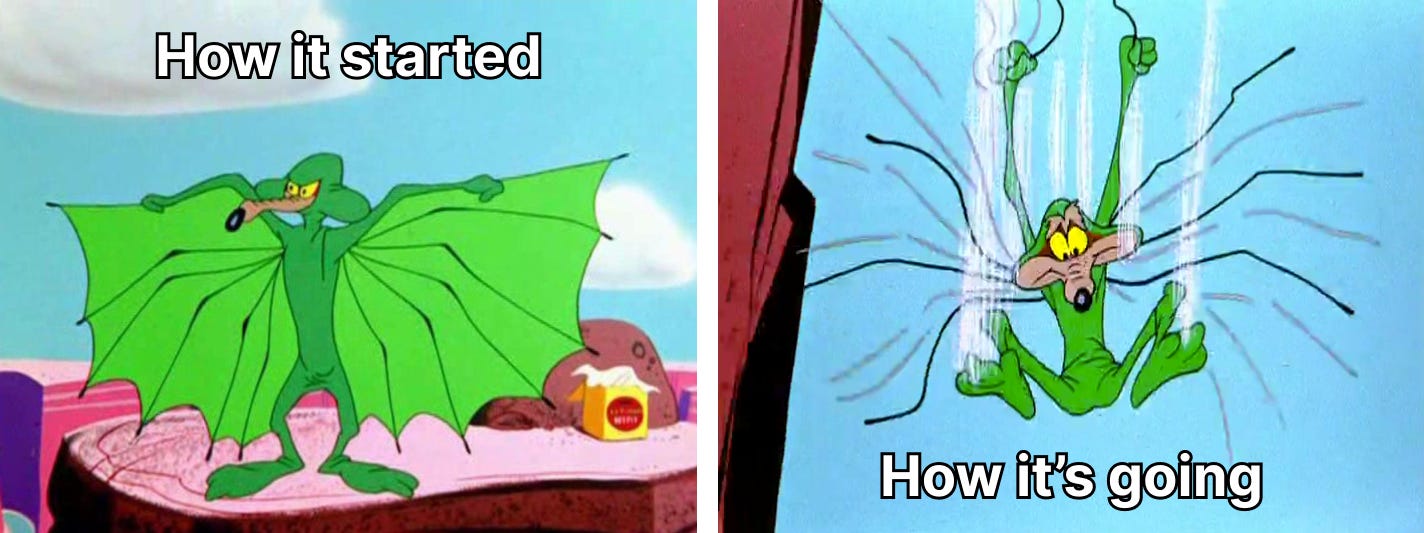

But I’ll leave you today wrapping up back where we started. If the only strategic approach you have is vision-based, then the only solution you have to the Vision Chasm is to come up with an even bolder, even more compelling vision, one that’s even more removed from reality. But if the vision is awesome enough, then surely it will motivate everyone to pull their socks up and leap over the damn chasm!

Absolutely – let’s see that in action:

Happy leaping!

Tom x

Ready for the next part? Tumbling into the Vision Chasm Part 2

Hungry for more on vision-free strategy already?

Listen to a recent podcast episode where Corissa and I talked about the story from this article and others – lots of clues in there for where we’re going next in this series: https://shows.acast.com/triggerstrategy/episodes/061-tumbling-into-the-vision-chasm

Grab one of the last spots for my free webinar The Complexity Gap on 17th July. I’ll be giving the talk I recently gave at UX London. In this, I talk some more about retrospective coherence and share a method for making progress using many micro-visions.

A meet cute is a scene in media, in which two people meet for the first time, typically under unusual, humorous, or cute circumstances, and go on to form a future romantic couple. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meet_cute

![[DEPRECATED] Trigger Strategy has become The Reach](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!CChb!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd6524a40-bedd-4b02-b1e6-d9adac56fa1b_850x850.png)

![[DEPRECATED] Trigger Strategy has become The Reach](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0a1A!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3d932af5-2274-4840-8a79-d4ee229a2a91_1344x256.png)

As noted LinkedIn Influencer Søren Kierkegaard once wrote:

“It is really true what philosophy tells us, that life must be understood backwards. But with this, one forgets the second proposition, that it must be lived forwards. A proposition which, the more it is subjected to careful thought, the more it ends up concluding precisely that life at any given moment cannot really ever be fully understood; exactly because there is no single moment where time stops completely in order for me to take position [to do this]: going backwards”

I love how you convey the overall idea of the Vision Chasm through a real-life story. And that you also show how we use **story** both to 'predict' the future (hopefully, yet hopelessly, through the vision) _and_ to 'explain' the past (through retrospective coherence). And you do it all in a story! Very meta but very compelling :)

The whole idea of vision/mission/goals really needs unpicking and I look forward to the rest of your article series. I think Peter Compo's Emergent Approach to Strategy can add nuance to that discussion. On the one hand, he does talk about 'aspirations', which can figure as vision/mission/goals in a strategic plan. But on the other hand the strategy emerges. Although he does 'work backwards' as you say, he focuses on the bottleneck, which is then 'busted' by a strategy (strategy←bottleneck←aspiration).

How would that look? To use your story, the first **aspiration** would have been 'We need to find our next S-curve'. The **bottleneck** is 'we don't know what the next S-curve should be'. The **strategy** is 'talk to real customers and explore many small ideas'.

One idea then emerges as one that seems to get traction. Now the **aspiration** is: 'Create a working product quickly that real customers will pay for today'. **Bottlenecks** include: 'We don't have time/money to design for pretty'. **Strategies**: 'Create the skeleton with a basic useful spreadsheet' and 'Update manually (Mechanical Turk style) before automated'. And so on.

Obviously, I'm now guilty of 'retrospective coherence'. Would the team really have chosen that first aspiration, or picked the bigger 'vision'? Would they have updated the strategy to the second aspiration and sought the new bottleneck?

I hope to explore some of these ideas with you on my podcast soon as it feels like you and Peter Compo are rowing in the same direction. Meanwhile, looking forward to the next article.